Designers are Metaphysical Mathematicians

There are probably as many definitions for “design creativity” as there are people who have knowledge of the concept. However, it seems that a large portion of the descriptions I’ve seen–which also forms much of the boilerplate on “creativity” by the companies claiming to “have it”–could be summed up as “Mystical flashes of insight from the mental void.”

In my experience, it sure seems that the ‘spark of insight’ which initiates the process of creating something new can seem to strike my mind as if it were a “bolt from the blue.” However, I think there is much, much more to a good description of insightful innovation than simply regarding it as “a mental miracle.” I think that the cognitive process which enables that spark of innovation can be described better and–this is what makes this goal so important–could potentially be taught and learned.

I think designers, good designers, are exceptionally strong conceptual thinkers. I think it is their understanding, explicit or implicit, of the conceptual nature of human thought which enables them to be so creative. By this I mean to say that designers can step back and observe a design problem at a more abstract conceptual level than most people. By doing this, they have a much broader view of the problem and can see far more avenues to solutions. But how do they do this? What is the cognitive process which enables them to do this?

People often think of themselves as either “left-brained” or “right-brained.” “Logical” or “intuitive.” Mathematician or artist. But is there really a dichotomy between the mathematician (rules, laws, concretes and the definite!) and the creative work of the artist and designer (inexplicable flash of genius from the mental beyond)?

As different as the two disciplines of ‘mathematician’ and ‘designer’ may seem, I think these two disciplines do share one thing in common: a love of variables.

Mathematicians, of course, love variables in the form of algebraic equations. One instance of their use of variables is in the simple equation of a line; a specific example might be: y = 0.5*x + 3. The variables in this equation are x and y, the numbers ‘0.5’ and ‘3’ are constants, and a unique value for x defines a unique value of y and vice versa.

How do the variables in the mathematician’s algebraic equation relate to the work which designers accomplish? Can the seemingly ‘purely intuitive process’ of ideation relate to the rigid world of mathematical proofs? I believe so! In creating concepts to answer a problem which is presented to them, creativity is enabled by a designer who regards concept features as variables. During the conceptual phase of the design process, designers are constantly tweaking the metaphysical features of their concepts–“adjusting their design’s variables”–until their concept fits the demands of the client.

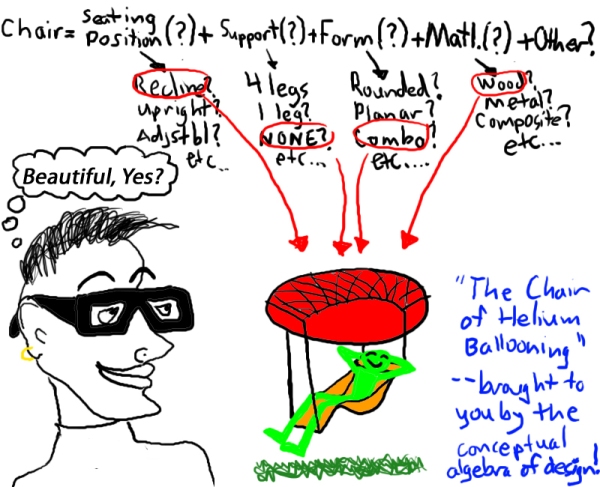

An example can help to clarify what I’m stating here. Suppose two people are given the same task: “Build a chair.” The first person considers his definition–his concept–of chair and then just immediately proceeds to build a four-legged platform for seating. But the second person, a designer, does not immediately proceed to replicate his concept of chair. The designer first considers his concept of chair and then engages in an inquisitive and iterative process which alters the features (variables) of his concept of chair, in order to come up with something completely new. His mental process might go something like, “A chair typically has four legs and supports a person in a seated manner. But can the number of legs be varied for a more effective solution? Can the legs be removed entirely–a chair suspended from the ceiling? Add or subtract armrests? The material of the chair can be varied–which material best suits the customer’s demand? Or has the customer not identified what he really wants yet? Perhaps the customer’s values are not clearly identified, which makes the problem definition itself a poorly defined variable in this project? Will the chair’s environment change? Will it be used indoors or outdoors–and how will this affect form and material selection?” In the mental process of this designer, I’ve italicized the terms which emphasize that the designer’s inquisitive and iterative mental mindset is the process of varying the metaphysical features of his design. The ideation process is essentially an endless process of “What ifs?” “What if we varied the material? What if we varied the number of legs? What if we adjusted the form of the chair? What if we rearranged the components? What if we wanted to seat more than one person?”

The designer is, indeed, a metaphysical mathematician–a master at identifying and adjusting the metaphysical variables which are relevant to his design problem. I do think it’s important to recognize the latter part of that sentence: if designers get a little too carried away with the idea that “anything can be changed!” then they’ll run hard up against some primary facts of reality (i.e., runaway philosophical subjectivism will crash a plane that must fly right into the side of the mountain), as well as potentially angering the client with an attitude suggesting that what he really wants is completely arbitrary: ‘anything goes!’ Nay, there is not much value to be gained by a designer supporting the mathematician’s stereotype of us: ‘Arbitrary Anarchists.’ Far better for us to identify what can be changed in the design, and then make the change if the alteration adds value for the consumer.

This constant, inquisitive process of asking ‘what if?’ should happen at all steps of the design process, but it is especially important in the early stages, when defining the problem which the customer wishes to solve. As suggested in the last few paragraphs, even the “constants”–the customer requirements–which form the context of the “design problem equation” can be variables if they are poorly defined initially. I think a crucially important capability which good designers have is the ability to draw out and define what the customer wants–to understand and give voice to what the customer’s values really are. This process, too, is achieved by the same conceptual process: regarding the customer’s goals and values as a variable–but just in the sense that they are currently poorly defined and must be fleshed out through good communication. “Do you really wish for us to just design ‘a chair’ for you? Or would a more flexible piece of furniture be more valuable to you–perhaps a chair which can morph into a bed, or adjust to seat more people?”

In the final analysis, I think designers can have just as much–if not more–of a mentally challenging job as a noted professorship in a prestigious university’s mathematics department. At least mathematicians will typically have the variables in their equation defined for them… The big challenge in design is that the problem’s variables often have to be identified by the designer in the first place–and that’s just the prelude to the large amount of work which goes into the conceptual iteration / “varying the variables” phase! But, on second thought, do the best mathematicians not do this same process as well?

So this, too, is true: anyone who aims to create something new–whether it be a mathematical theorem or a revolutionary new product–is readying themselves for this “conceptual algebra.”

I’d love to hear what anybody who stumbles across this thinks of what I’ve written here… Does this description of “the creative cognitive process” accurately describe the ideation process which you go through, when designing?

– Justin Ketterer

Addendum: This write-up is an overture to an essay I plan to write on epistemology and design; I could even see it developing into a book. The implications for helping people clearly identify the mental process which enables creativity are BIG… More people who are more creative will enable an increase in our own well-being! If more people are made aware of the thought process which can enable them to be more creative, then we’ll have a vast increase in the number of people who will be creating ‘valuable mechanisms’ in every discipline imaginable–and in disciplines not yet imagined(!).

I should note that the analogy of comparing the process of concept-formation to algebraic mathematics is not of my own invention–it is the central idea posited by Ayn Rand in her Objectivist philosophy’s theory of epistemology.

EEEEEEK!

Yes, Yes… I’m aware that the mention of that name may polarize and repel some people who read this. The polarizing effect which Rand’s name has on people is largely due to her stalwart defense of laissez-faire capitalism… Her arguments for that socio-economic system were based on her thoughts on ethics, which were consequential to her thoughts on epistemology.

I think it’s very unfortunate that most discussions of Rand’s ideas focus strictly on her polarizing views on ethics and politics–while largely not discussing her thoughts on epistemology (the latter of which formed the basis for this essay). If, up to the point where Rand’s name was mentioned, you were entertaining the ideas with relative equanimity, please continue to do so. Leaving aside the reaction which the idea’s origins may engender in you, please let me know what you think! This blog is about the design and engineering of products; I wanted to share the remarkable parallels I’ve noticed between my experiences in design and Rand’s theory on concept-formation… What do Industrial Designers, Mathematicians, and Ayn Rand have in common? It seems that there is quite a lot!

Please, I’d rather leave nasty debates on “the merits of capitalism” for other forums :-\…

– Justin

Justin, excellent article and interesting perspective. Thanks for logging onto SmartStorming and for your comment on our recent post.

We’re enjoying this article-based dialogue on a fascinating subject.

Check out our new post here – http://blog.smartstorming.com/2009/05/08/can-creativity-be-taught-part-two-mastering-the-creative-process/

Based on what you’ve written, I think you’ll find it interesting.

Keith & Mitchell

http://www.SmartStorming.com

Keith & Mitchell,

Thanks, and I really enjoyed your “part-two” essay especially. Identifying and understanding the criteria which will enable creativity (cognitive mechanics and design problem definition) are very interesting topics to me, and you addressed them in that post.

I plan on writing a follow-on article to this blog post. While this essay emphasized the general method of cognition which enables creativity (viewing concept features as variables), the next one will go into more detail about the process of conceptualization within the context of the problem definition. Thanks for stopping by!

Great article on a topic I have enjoyed contemplating myself. I also want to check out the SmartStorming links.

After reading your post, and upon introspection of my own design process, I think that what you describe above seems to be two distinct forms of ideation.

The first is the bolt from the blue (I personally think of this as my being slapped by a Muse) and the second is the methodical solving of a design problem. While I think they must be related, and do feed off one another, they are distinct.

The former, I would characterize as the subconscious sending an idea up to my conscious awareness. It usually involves the integration of some concepts/objects/ideas that I have been aware of but had not previously connected in that particular way. I think of this as not unlike a dream, where the subconscious knits together a series of items from your conscious awareness and creates a narrative out of them. Usually the design ideas that I get this way make more sense than my dreams, but it can vary 🙂

The latter is the direct application of logic and conscious focus, and this is where your analogy to mathematical variables comes in. I had never thought of it explicitly in this way, and I like your analogy quite a bit. A designer can input certain values and solve for the other variables and get very different solutions. This would be an interesting problem to give a group of students – assign them different values for a set group of variables and compare the outcomes for how they ‘solved’ the other variables. This makes the designer a kind of practitioner of selective measurement omission, to continue Ayn Rand’s Theory of Concepts. I like this idea a lot.

I agree with you completely about the importance of the translation of the client’s requirements (an architect would call this the ‘program’) into variables in the design equation. I am convinced that somewhere in this part of the discussion there is a link to an aspect of this that I have been pondering for a long time, which is the relationship between conceptual thinking + problem solving on the one hand, and a designer’s personal style + design aesthetics on the other. I know that once the concept of aesthetics is invoked things can get slippery, but I am convinced that there is a link between epistemology and aesthetics.

The manner in which the designer translates the program into a set of design variables is inextricably linked to his aesthetic values. It’s not quite a thesis statement but it’s close.

One point you raise that I’m not completely sure I agree with (although I could be convinced) is the link between a great designer’s ability in conceptual thinking, and his explicit or implicit understanding of the conceptual nature of human thought. While I agree that a proper teaching of the conceptual nature of human thought would produce better designers, I can’t help but think of the example of Frank Lloyd Wright. While he was clearly an exceptional genius as a designer, most of his writings on design dissolve into the mush of spiritual musings. He had an incredible ability to conceptualize very complex and abstract designs, but I don’t think of him as having a strong grasp of the mechanisms of conceptual thought as such. If you think he is the ‘implicit’ example then I would be interested in your thoughts on this (and it can wait until after your thesis is done.)

Finally, I dig the venn diagram, now you just have to solve for the big red question mark!

Earl,

Regarding the conscious/subconscious, I see what you are saying: drawing a new concept out of disparate ideas to create something new happens, in my experience too, like a “flash” inside my head. For me, what enables the “aha!” moment is what I wrote up here: the mental mindset in which I question the fundamental features of an idea and ask: “Well how could this concept be varied?” It’s after I consciously choose to engage in “varying the variables” that I then get that “mental flash of insight.” It’s kind of like a mental attitude which frees my mind from dealing with lower-level conceptual concretes and allows my brain to range over a bunch of different ideas which I normally would not consider. Perhaps it’s different for you?

And perhaps what you bring up is really what I should be focusing on if I REALLY want to describe creativity: what happens IN that instant when you make the mental connection which enables creativity? I’m sure there’s value in describing the “mental mindset,” which enables the flash of insight, but a thorough analysis would require studying the two cognitive processes you mention, they do seem like different mental processes. I think the first (which I already described here) is abstracting to allow features to be varied, and then the second “flash of insight” is swapping various features in and out of your concept, mentally. Differentiation and integration. Where do those “various features” come from? Experiences? Our mind’s eye in “conceptual variable overdrive?” It kind of seems like it’s both, in my experience.

Regarding Wright, I would suspect(?) he had an implicit understanding of what we’re discussing here. A key feature of the creative process which I spent little to no time discussing in this essay was the context and purpose for creativity: the design problem itself. When we talk about “good design,” we’re saying that the “design was good” with respect to achieving some purpose. It sounds like Wright MUST have had an implicit understanding of the conceptual nature of thought… He must have had the ability to abstract away from the initial problem definition to the crux of the task and then deal with it accordingly. This process will be a major theme in the follow-on essay.

I might deal with aesthetics in another essay after that. Like you said, evaluating aesthetics gets very tricky, since personal tastes tie into the whole constellation of a person’s values. It’s a very personal thing.

And yeah… Probably won’t be able to write anything big until mid-July. I’ve got a few drafted notes on things I’d love to write about but won’t have time until then. 😦

One more thing I forgot to mention: when I was in undergrad architecture school (Washington U in St. Louis, in the late ’80s/early 90’s) the buzzword for a designer identifying an non-obvious variable and incorporating it into his design solution was ‘problematizing’.

Here’s the example that comes to mind: we were given the task of designing a small housing complex. One student designed a clever way of housing the trash dumpsters such that they were conveniently located for pickup, and yet hidden from view from both the street and the units. Nowhere in the program brief were dumpsters mentioned, and the student was praised in the final reviews for having problematized where to put the dumpsters and solving it so elegantly.

Its kind of a clumsy word but a useful concept. I don’t know if that word is really used any more, I can’t recall having heard it in a long time. It might have just been something that was coined by one of the instructors there.

I like that–and agree that a more elegant word is needed for such a crucial aspect of creativity!

Hi Justin,

As a graphic designer, I found this post really interesting! It’s nice to hear someone thinking about creativity from an Objectivist perspective. I’ve thought about it, but have never made the time write my thoughts out, preferring to spend my time designing and oil painting. I don’t have a lot of time to write right now, but I just wanted to say thanks. There are not many people who really respect the creative process, and I’ve found that even some of my fellow Objectivists tend to see creative types as floaty, abstract idealists – a label that doesn’t describe me at all!

Again, thanks for writing this. All the best.

Kelly Koenig

Kelly,

Good to hear from you, and thanks! Feel free to use it whenever the boobs who conflate creativity with froot-loopy hogwash need to be countered, and whose numbers are legion. I’ll let you know when I write the follow-up for this.

– Justin

Your article was forwarded to me by my son, an Industrial Designer. You articulated so well what he often tells me. I finally came to the conclusion, a while back, that he just inherited the best skills from each parent. Theres no way to explain his propencity for details, (such as math,) and his creativity. Other than his Dad always measured, leveled and followed a plan. His Mom on the other hand, flew by the seat of her pants, used bold color, and excelled.

Now that I have read your article…………you “hit the nail on the head”. All of you are just brillant!!

Sheila,

Wow, thanks! That’s a pretty fantastic complement, and it means a lot to me. I’m very glad that the essay was able to convey what I wanted it to–a clearer statement of the process of creativity. I’ll let you know when the follow-on essay is published here.

– Justin Ketterer

A somewhat related article that I found interesting.

Justin, Congratulations on your masters.

About mentioning Ayn Rand being seen as a negative: In my first job as an Engineer/Scientist at Douglas Aircraft, I was called “Howard Roark” by ID management as a negative. I got the feeling that it was because independent thinking made them nervous.

Seeing your crack propagation work on carbon fiber reminds me of when, at DuPont Engineering Thermoplastics, I did an FEA of a small bubble in a tensile test strip of molded nylon. The stress at the middle of the bubble was 17 times the crosssection stress. The classic Formulas for Stress and Strain book said it was 2-3 times. But I wasn’t allowed to publish the discrepency as a Phd boss told me, “The giants who wrote the book in the 20s and 30s are not to be put down.”

Good luck on your future career.

Bill,

Thanks! I’ll be defending in two weeks, and I’m stoked to graduate–though the job hunt continues…

17 times net section stress??!! Wow. Have you since seen publications corroborating your work? I’ve seen The Anointed Fracture Mechanics Theory of Yore which says “three times net section stress at the edge of a hole,” but theories are only as good as their assumptions–and how well they reflect reality. I think that’s been one of my major lessons in working on my master’s–always understand the assumptions of whatever model you are using. What kind of scale were you modeling? Did it account for plasticity? I mean, a stress concentration factor of 17 would get you well into plasticity and (highly localized, perhaps?) rupture for extremely low loads.

I can see how Rand’s philosophy could be a liability for me if I encounter people in the workplace who are beyond the point of discussing it reasonably (and, barring their googling me and finding this website, I’d probably just keep it under my hat anyways). I hope it will be an asset overall. Hopefully, an impersonal appeal to reason and the facts will be the modus operandi of whatever work environment I end up in. An office free of politics? Maybe now I’M the one being irrational, haha.

Good to hear from you.

– Justin

Justin, I modeled a standard tensile test strip of nylon. I did the FEA using the Cray computer as I needed a lot of elements to get a smooth and very accurate result. We used Pro-E for modeling and ANSYS for analysis. The bubble was about 1/16″ diameter. We used Poisson’s ratio to get a plastic modeling of the load reaction. Any value, even a one pound load, told the story on the stress concentration. I never saw anyone else’s work on this subject.

The lab let me do stuff on my own. (I learned a lot about engineering thermoplastics over 15 years and then got early retired just when I was proficient in computer analysis after many advanced classes around the US over a period of ten years.)

The Experimental Lab experts in making new plastics would compress to 70,000 psi the plastic as it was molded to make the bubbles so small you didn’t relly notice them. The bubbles where still there, though. High stress concentration was there too and it was bad for the real-world application designs I worked on like roller blades, bike wheels, athletic shoes, etc.

I went to Purdue for my BSME and Art Center for my BSID. The hardest thing was the different cultures at the firms. I worked for about two years at Douglas Aircraft, Westinghouse – Major Appliances and Elevator Div., and Amtrak; seven years at consulting; and 15 at DuPont. Each firm, like my first real job when I was in the USMC for three years, had their version of reality. And, like GM, which was owned by DuPont until the 1958 divesture, no one wants to or can change the bad karma. So the result is decline ending in death. One enlightened guy, Iron Man or Howard Roark, as long as he is alive, can make it a success. I always strived to work with enlightend leaders.

All the Best, Bill Marks